|

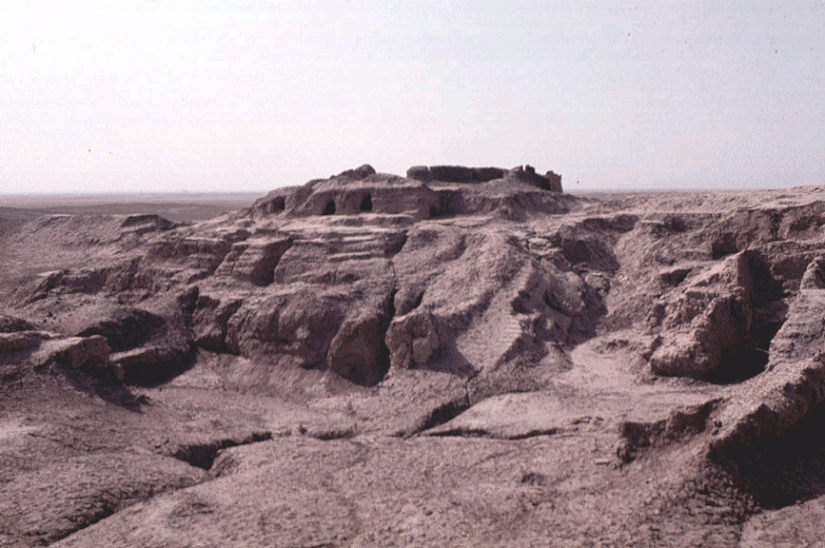

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online) Ancient Uruk -- Biblical Erech -- Arabic Warka Selected Excerpt on Uruk Overview: Known today by the Arabic name of Warka and in the Old Testament as Erech. When the city was occupied in ancient times the waters of the Euphrates River flowed close by; today the river flows some 12 miles distant -- having shifted its course through the millennia ... Uruk was one of the major city-states of Sumer. Excavations by German archaeologists from 1912 onwards have revealed a series of very important structures and deposits of the 4th millennium BC and the site has given its name to the period that suceeeded the Ubaid Culture and preceeded the Jemdet Nasr Period. The Uruk Period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and in the ensuing Early Dynastic Period it was by far the largest settlement known up to that time. It seems to have started as two separate settlements -- Kullaba and Eanna -- which coalesced in the Uruk Period to form a town covering circa 80 hectares; at the height of its development in the Early Dynastic period the city walls were circa 9.5 kilometres long -- enclosing a massive 450 hectares and housing some 50,000 people. The city remained important throughout the 3rd millennium BC up until the decline of Sumer itself circa 2000 BC. It remained occupied throughout the following two millennia down to the Parthian Period but only as a minor centre. Uruk was the home of the epic hero Gilgamesh and played an important role in the mythology of Mesopotamia to the end (AHSFC).

Chapter 1 Introduction

Despite its importance to the understanding of the development of early complex civilisations in the Near East, the Late Chalcolithic has been described as “one of the most ill-documented in Mesopotamia” (Jasim and Oates 1986:357). This is still particularly true for southern Mesopotamia, as excavation has been limited to only a few Late Chalcolithic sites apart from the city of Uruk itself (Akkermans and Schwartz 2003:184), partly due to the fact that many settlements have been long-lived enough for Late Chalcolithic levels to be buried under many metres of later occupation levels.

3.1.1. Chronology of early Mesopotamian civilisations

3.1.3. The role of exchange in the development of complex society

3.2.2. Northern Mesopotamia

3.3.1. Southern Mesopotamia

3.3.2.1. The "Uruk Expansion”: theories and explanations Among scholars arguing for a Late Chalcolithic exchange network on a much more equal level between the south and the north are Frangipane and Stein, excavators of the local northern settlements of Arslantepe and Hacınebi, respectively, who argue not only for the presence of evidence for a much higher level of socio-political complexity in the local northern communities than Algaze hypothesizes but also for the absence of evidence for southern domination of these communities. Frangipane (1997:46-7) is reluctant to believe that polities in the south were able to control an exchange system on this geographical scale, a view she shares with Johnson (1988-89). Frangipane argues that large northern centres such as Nineveh and Tell Brak would have “neither the physical nor the political space for an alien settlement” (Frangipane 1997:47). In contrast to Algaze, Frangipane (ibid.:48) argues that the success of the Uruk exchange system, which she interprets as the intensification of already existing exchange contacts (Frangipane 2002:129), was due not to the domination of less socially complex northern communities by southerners but to the fact that some northern settlements such as Arslantepe were already well-organised regional centres, exercising the control of the local populations needed to ensure the necessary flow of goods. Stein (2000, 2001) is of the same opinion and argues that northern settlements merely intensified trade relations by the time of the arrival of southerners. Rather than being overtaken by the southern settlers they were able to control the level and pace of interaction with the southern settlers and to maintain their cultural identities. Rothman (2002:58) agrees with both Stein and Frangipane in the argument that the southern Uruk presence in northern Mesopotamia should not be viewed in terms of southern dominance or colonialism. On the contrary he argues that the ”Uruk Expansion” represents an increase in economic exchanges between the two regions to the benefit of both north and south. Northerners are not expanding south because they inhabit less developed societies but because they do not have to, living as they do in the resource-rich north (ibid) ... With the abundance of raw materials and the high level of technology in the north it is questionable whether the southerners had anything to offer of particular attraction to the northerners (Stein 2000:20). Schwartz (1988) uses the analogy of the 8th century BC Greek colonisation of the Mediterranean (ibid:9) to suggest that the expansion of southern Mesopotamian settlements to the north was related to overpopulation and major social changes in the south and was aimed at control of agricultural land rather than control of trade routes. Johnson (1988-89) has argued that the colony sites are simply too large, too elaborate and too many to merely function as trade stations (a point shared with Akkermans and Schwartz 2003:204) and suggests that they may have housed refugees from the southern plain, having fled the southern cities after political unrest or as Schwartz (1988) argues, in search of land.

3.3.3. Evidence for north-south interaction ... Northern Mesopotamian settlement patterns did not show any effect from the presence of southern Mesopotamian settlers with several northern sites, including Tell Brak, already in multi-tiered settlement patterns by the time of contact with southerners (Lupton 1996:34). Though Algaze (2001b:66-8) argues that the northern societies had not reached the level of organisational complexity equivalent to that in the south, evidence from both Hacınebi and Tell Brak are sufficient to show that northern Mesopotamian communities had a high enough level of organisation not to be exploited or otherwise economically or politically affected by contacts with southern Mesopotamia. Rather from the archaeological evidence it appears that the northern settlements merely increased trade relations with their neighbours, probably to their mutual benefit. Judging from the available evidence and the long history and obvious importance of inter-regional exchange in Mesopotamia, the function of the southern colony and enclave sites in the north appears to be primarily connected with trade. Southern Uruk enclaves on already inhabited local northern sites are unlikely to have been set up in order to exploit land for cultivation or grazing, as this would mean competing for land with the already established local communities. For the Bibliography See Link (1) or PDF ...

(1) A Thousand Years of Farming: Late Chalcolithic Agricultural Practices at Tell Brak in Northern Mesopotamia by Mette Marie Hald --- BAR International Series (2008)

The Uruk Phenomenon: The role of social ideology in the expansion of the Uruk culture during the fourth millennium BC by Paul Collins (2000)

|